Pervasive discrimination persists throughout society, and in the workplace.

Most of the Black American business leaders (90%) we surveyed report personal experience with discrimination based on their race. While the numbers of people who have experienced bias at work aren’t as high, they remain shockingly bad: 56% say there is discrimination at their workplace against Black people, and 33% say that race is the primary driver of discrimination they have personally experienced at work. Given that, it is perhaps unsurprising that only have as many Black business leaders feel are less than half as likely to feel empowered to overcome professional challenges as their White counterparts.

Black leaders in business: Hope, anti-racism, and the struggle for equity

Business in America faces a moment of reckoning. Racial inequity, long endured and long decried by those most affected, has moved to the front of corporate, social and political agendas, even as Black Americans face continuing assaults.

The coronavirus pandemic hit the Black community with disproportionate impact, both in terms of the health toll and the economic toll. Concurrently, a wave of violence crested, crystalized by the tragic and brutal deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, among other Black Americans. The widespread social justice protests that followed were often met by hostility.

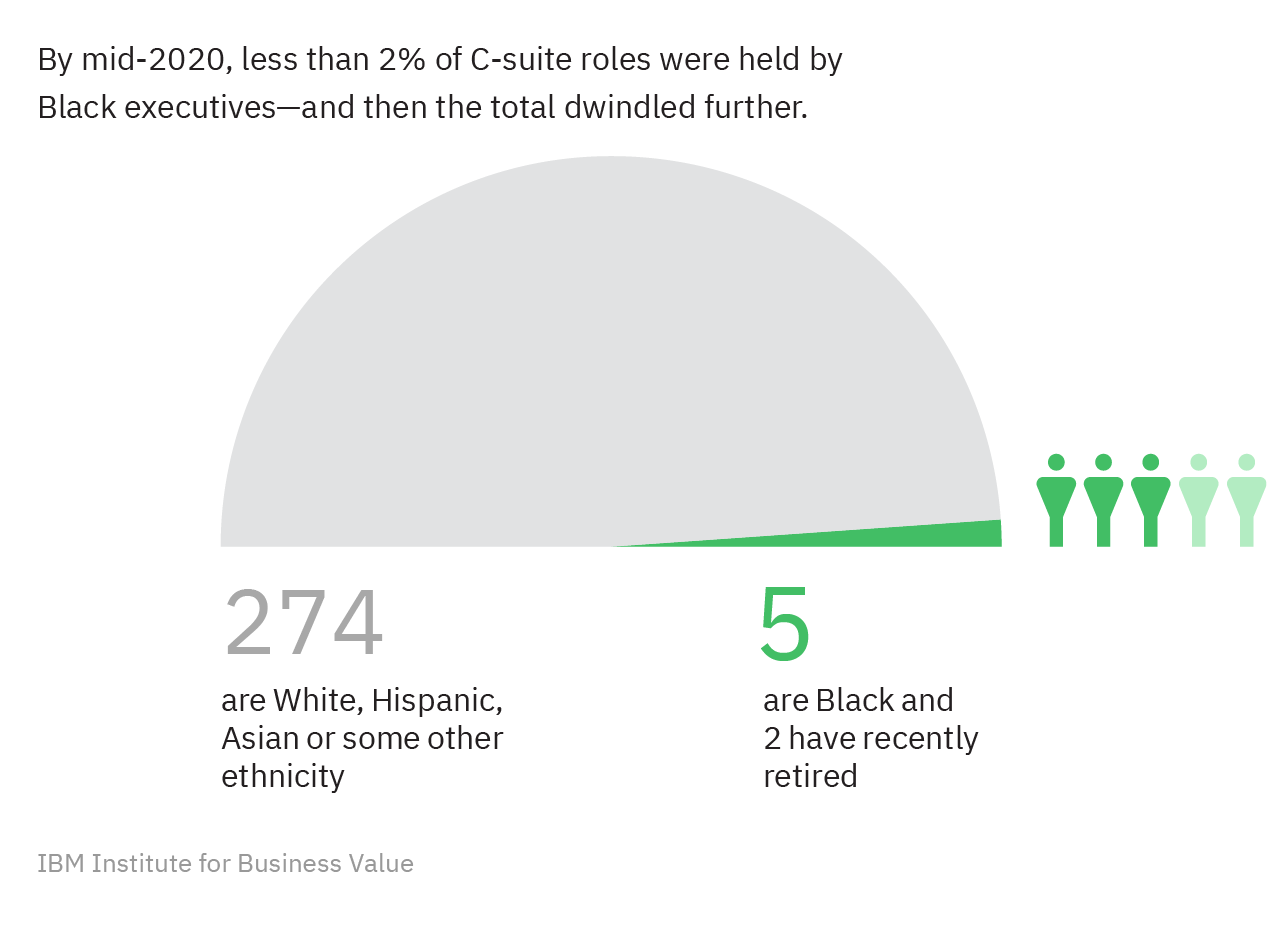

Many business leaders have taken steps in response, announcing new and enhanced diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) and anti-racism programs. After years of keeping silent, many Black executives are openly sharing—for the first time—their experiences of racism with their co-workers. Yet corporate America’s top ranks look nothing like the country they serve. Of the 279 top executives listed in proxy statements for the 50 biggest companies in the S&P 500 in July 2020, only five, or 1.8%, were Black, including two who recently retired.

Exceedingly disproportionate

Perspective

Perspective

Black history in America, typically omitted or overlooked, often requires extra work from Black people to retell the narratives, add vital context, and infuse years of collective cultural wisdom to understand present-day conditions. Black Americans are in a unique position because Black is both a race and an ethnicity.

We use the term Black to be more inclusive of the culture and community, and specifically to recognize people of African descent who live in the Caribbean or West Indies, as opposed to saying African-American. When Black people were taken from Africa and spread out all over the world, their unique identity and culture was stripped away upon arriving in America. Descendants of slaves emerged with new cultures depending on their location—those locations are what informed their culture.

A sense of place has deeply shaped Black history and culture. The Black Migration sets Black people apart from other races and created different cultures within the Black community. By separating Black people by race and region, Black Americans forged their own history, culture and society against unimaginable odds.

The entire history of America has been based on racial categories and determined where you can live, who could own land and how you were taxed. And we can’t tell the story of America without telling the story of Black people and their contributions in shaping America’s identity from technology to music to food to fashion and popular culture.

However, we live in a society where Blackness is often associated with negative traits. A society where racism and racial anxiety has existed for more than 400 years. Class and economic anxieties do not erase racial ones in our current climate with COVID and social unrest—they transcend these anxieties.

Amid the turmoil of 2020, the IBM Institute for Business Value (IBV) surveyed more than 1,500 Black executives and business leaders, between May 220 and January 2021, comparing the results to a similarly composed survey of White executives and business leaders. The results point to continued obstacles for Black Americans, as well as glimmers of hope that improvement and progress is underway.

The Black experience in business is still vastly different than that of their White peers. The evidence is startling.

Our survey shows that:

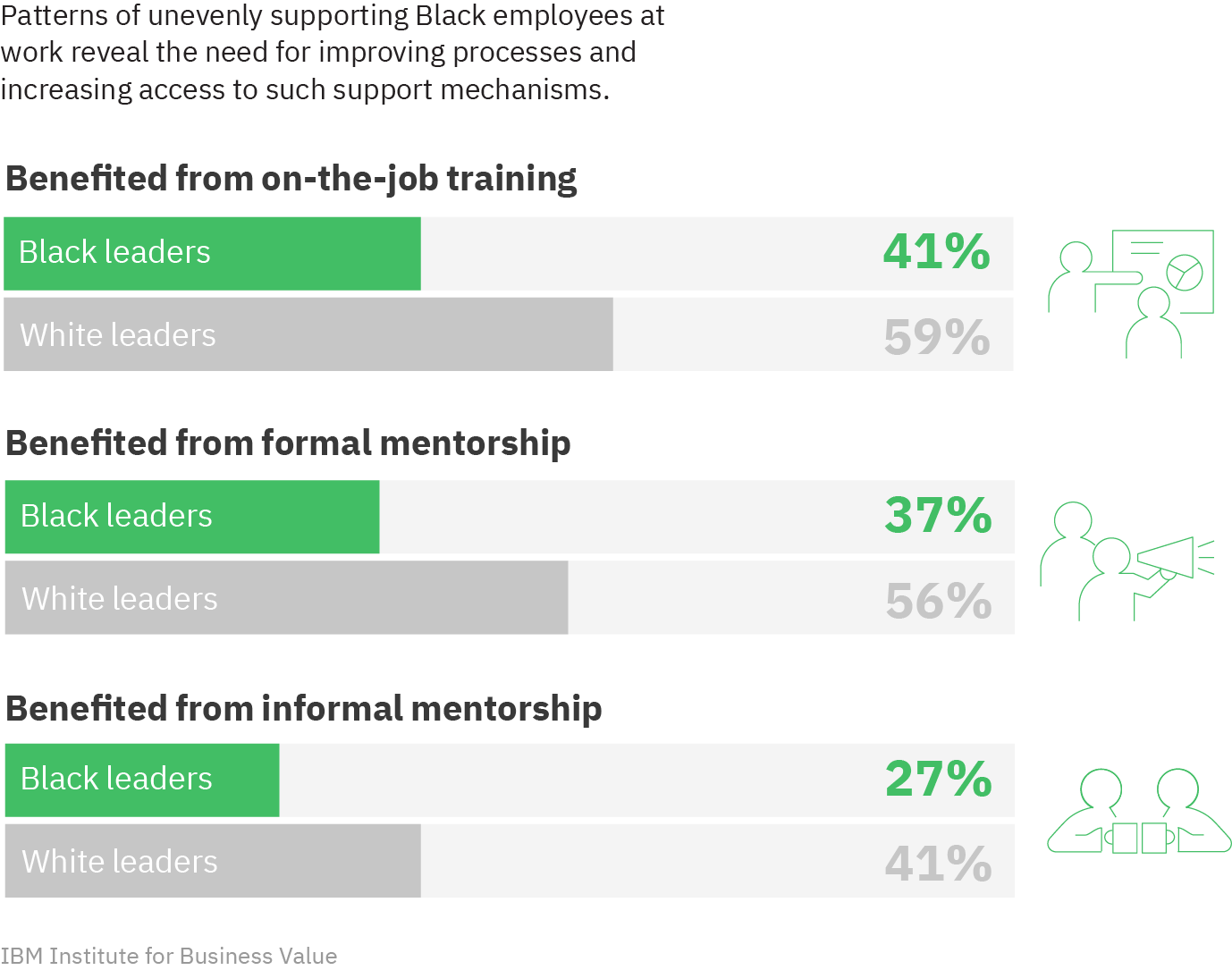

Career support for Black professionals is inadequate.

Black business leaders point to the criticality of mentoring, sponsoring and other career support as essential contributors to success. Yet our survey reveals that far fewer Black than White workers experience workplace benefits such as on-the-job training, mentoring, and employer-funded continuing education.

Anti-racism has established a toehold.

If there is a silver lining to persistent workplace discrimination, it is recognition by White business leaders of the challenges facing other populations. In fact, 76% say they believe racial bias exists in society, and 51% of White survey respondents acknowledge there is discrimination against other racial and/or ethnic groups at their workplace.

And wellness efforts aren’t connecting.

With Black Americans bearing the brunt of COVID-related health and job impacts, corporate commitments to wellness are of particular importance. Unfortunately, those efforts are not connecting. In another recent IBV study, 80% of executives reported that their companies were supporting the physical and emotional health of employees; however, only 46% of employees agreed.

And yet, corporate diversity efforts lag aspirations.

In IBV’s recent 2021 CEO study, CEOs expressed strong positive conviction that a workplace championing diversity and inclusion (D&I) is a central criterion for leadership. But when it comes to putting that conviction into action, D&I was noted as a measurable part of financial performance by only one in four respondents. Among the most important organizational attributes for engaging employees, D&I ranked near the bottom of a 13-choice list.

The technology gap must be closed.

Analysis of the data suggests that Black executives are more apprehensive about new technologies than their White counterparts, and are more wary about how those technologies are being developed and made available in their communities. Given that technology is consistently identified as the most important factor for future competitiveness and success in the IBV’s 2021 CEO study, this is a gap that must be closed.

But corporate efforts here aren’t meeting expectations either: While 74% of executives in another recent IBV study report that their organizations are providing adequate training on how to work in new ways prompted by the pandemic, only 38% of employees agree.

Data shows that Black professionals face obstacles to achieving success that begin in primary and secondary school, and extends from the consumer marketplace to government and public services. The fact that our survey respondents have succeeded in business makes their perspective all the more insightful and important.

It also underscores the missed opportunities, for both individuals and businesses, in not engaging more Black talent. The shortcomings that exist in corporate environments limit the performance potential and business impact of a critical segment of the business workforce. Addressing these shortcomings requires ongoing and concerted action..

“Diversity is a fact. Equity is a choice. Inclusion is an action. Belonging is an outcome.”

—Arthur Chan

Black Americans in the workplace

Black American business leaders in US workplaces surveyed by the IBV comprise a wide spectrum of professionals—senior executives, senior managers, junior managers, and entrepreneurs. These individuals have already achieved professional success and are on a career path to achieve even more. One of the goals of this study is to identify the behaviors, tools and motivations that help fuel these success stories.

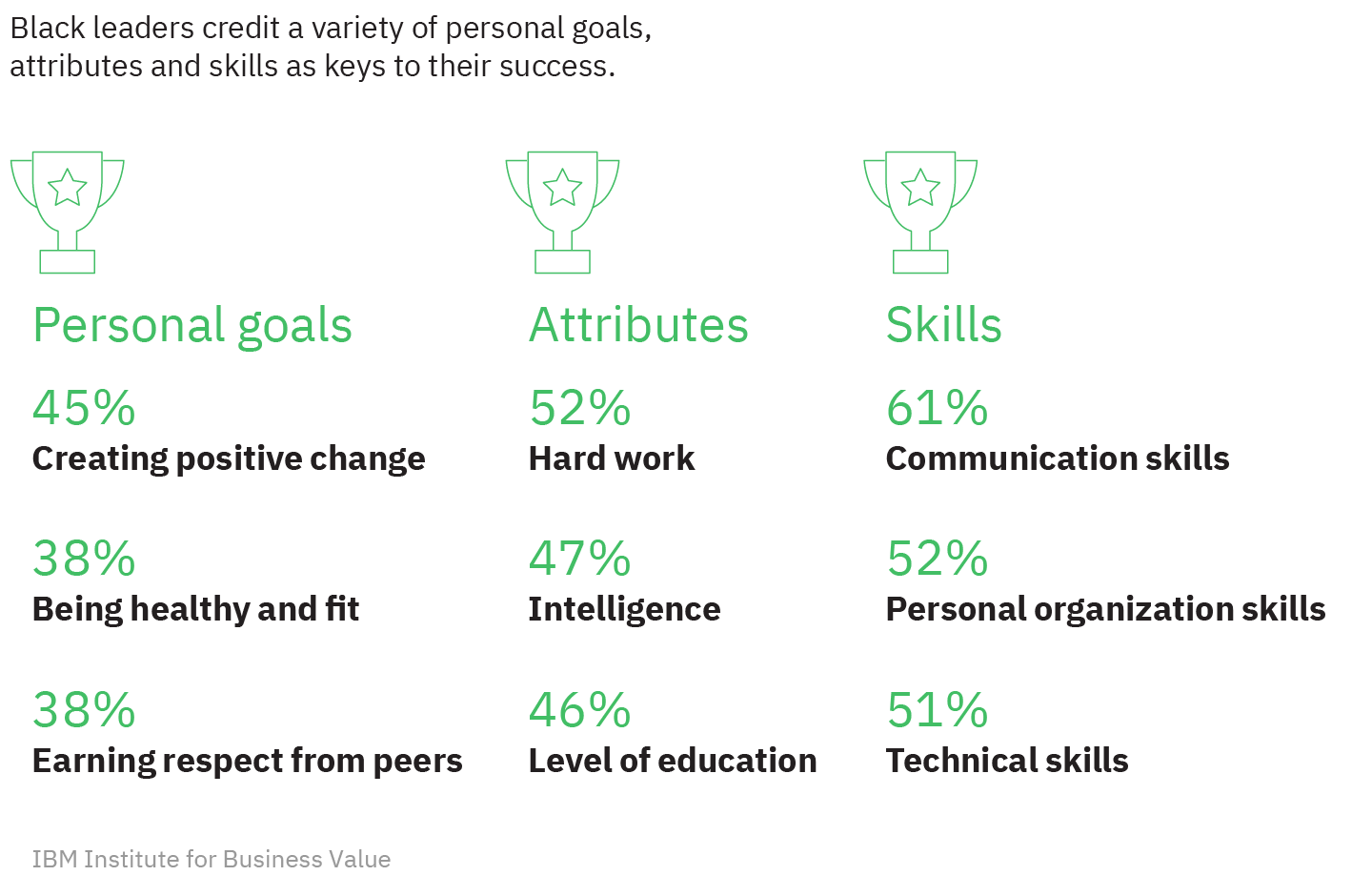

So what is it that has driven business success among these Black business leaders in the US? The #1 motivation cited by respondents is passion for their job. The #1 goal: creating positive change—ranked higher than other self-motivated objectives, such as achieving financial security, power, or even personal happiness.

As a group, the Black leaders we surveyed are committed to having a positive impact. They cite hard work and intelligence as the most important personal attributes that contribute to success in American society. And they rank communication skills and personal organization skills as #1 and #2, respectively, as the most important skills for success.

What fuels success?

In terms of behaviors and practices, the top-cited activities that fueled their personal success are continuous learning, goal-setting, and team-building. The people most influential in inspiring their success: other business leaders, who are rated even higher than respondents’ own parents. This latter point underscores the importance and impact of business-based role models and mentors in inspiring Black American success stories.

And this is an area where businesses can make an immediate and tangible difference. According to our survey, only 41% of Black American business leaders say they have benefited from on-the-job training or skilling, compared with 59% of White business leaders. Only 37% of Black leaders say they’ve benefited from formal mentorship, and 27% from informal mentorship, versus significantly higher 56% and 41%, respectively, for their White counterparts.

And that pattern continues, whether related to sponsorship or employer-funded continuing education. In precisely the areas where promising Black talent might be most activated, employers are consistently falling short, unevenly applying their support mechanisms.

The greatest inspiration for Black business leaders' success is other business leaders. This reflects the importance of business-based role models in Black American success stories.

Room to improve

Discrimination in the workplace

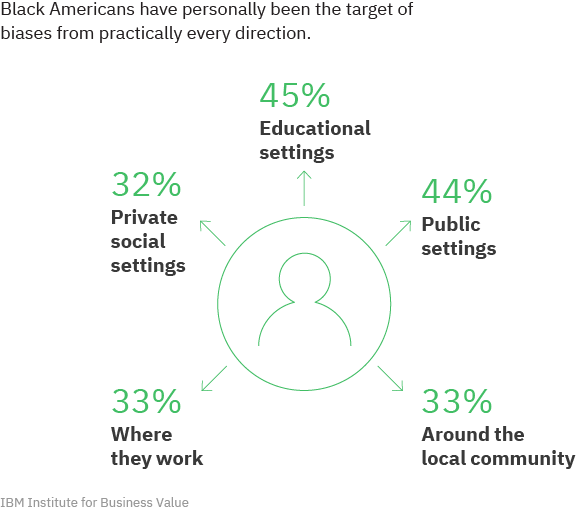

When it comes to the deeply disturbing personal experience of discrimination, 90% of Black respondents reported personally experiencing discrimination because of their race at some point in their life journey. Race-based bias far outweighs other biases based on gender, socioeconomic status, political views, age, sexual orientation, or any indeed any other factor we measured.

45% of respondents say that race was the primary driver of discrimination they experienced during school, 44% in public settings, 32% in private social settings, and 33% in their local community.

The workplace may be less biased than some other areas, but not much: 33% of Black respondents say that race/ethnicity has been the primary driver of discrimination they experienced at work. And they report having to work harder to succeed because of their identity. 58% of Black leaders say America is unequal today versus 29% of White respondents and 56% of Black leaders tell us that things are not improving over time. It’s disheartening: they believe their experiences with discrimination are similar to those of previous generations.

Organizations have struggled to create inclusive environments where Lakeisha and Darnell feel comfortable bringing their whole selves to work the same way that Emily and Greg do.

Black Americans rarely fit comfortably into workplace culture, especially when that culture is determined by White faces and spaces. Blackness is complex. The diaspora created by the African slave trade resulted in the development of unique Black cultures, experiences, perspectives, and schools of thought. Tom Burrell, founder of one of the first all-Black ad agencies in the 1970s, puts it best: “Black people are not dark-skinned White people.” While that might seem enormously obvious, organizations have struggled to create inclusive environments where Lakeisha and Darnell feel comfortable bringing their whole selves to work the same way that Emily and Greg do.

Bias all around

Perspective

Black people who wish to climb the corporate ladder in the US invent ways to tailor their looks and mannerisms so they can function in the culture of their largely White workplaces as they strive to survive, be visible, and advance. Survival methods fall into three categories: code-switching, covering, and creating cultural capital.

Code-switching refers to how someone adjusts their style of speech, appearance, behavior, and expression in ways to make others feel comfortable with them in exchange for fair treatment, quality service, and employment opportunities. Black people are taught at an early age to learn how to code-switch in order to survive police interactions, interact with teachers at school and collaborate with students and friends.

Code-switching is not reserved to only Black people, but other races as well. However, dozens of research studies suggests that code-switching is a key dilemma a Black employee faces around race at work. While it is frequently seen as crucial for professional advancement, code-switching often comes at a great psychological cost. If leaders are truly seeking to promote inclusion and address social inequality, they must begin by understanding why a segment of their workforce believes that they cannot truly be themselves in the office, then take action to create a more inclusive environment.

Covering is another form of survival for Black employees. Covering is a term coined by Dr. Kenji Yoshino, Chief Justice Earl Warren Professor of Constitutional Law at NYU Law and Director, Center for Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging. Covering is a strategy through which an individual downplays a known stigmatized identity to blend into the mainstream.

There are four concepts of covering which individuals downplay: appearance based, advocacy based, affiliation based and association. According to Dr. Yoshino’s research, more than 61% of employees in the workplace cover across all four concepts. Nearly 80% of Blacks in the workplace cover around appearance, grooming and mannerisms.

Covering demands a culture of conformity which leads to diminished employee commitment, which results in weaker performance. Black people do not feel psychologically safe enough in the workplace when they are their authentic selves, so they cover in hopes of having an opportunity to be seen and heard.

Creating cultural capital. Because they have been largely marginalized in White workplace culture, and afraid they are always “one mistake away” from losing everything, Black people have created their own experiences affirmed by their peers. They create cultural capital with its own sense of Black pride and status. They also create community cultural wealth which is an array of knowledge, skills, abilities and contacts possessed and used by communities of color to survive and overcome racism and other forms of oppression.

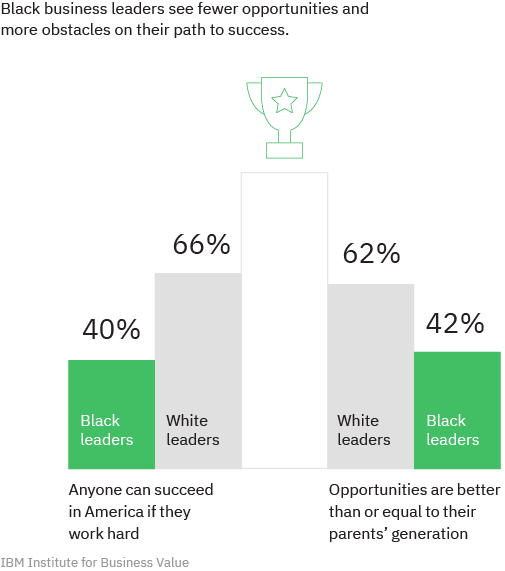

When rating their organization’s D&I efforts, Black business leaders cite these initiatives as inadequate at a 50% higher rate than their White counterparts. While 66% of White business leaders say anyone can succeed in America if they work hard, only 40% of Black leaders surveyed agree. 62% of White business leaders believe their opportunities are equal to or better than that of their parents’ generation, versus only 42% of their Black peers.

All of this disturbing evidence necessitates a call to action. But it is a call to action still only recognized by half of the White business leaders surveyed. Despite decades of legislation and cultural change, and the horror of recent incidents of bias and brutality, discrimination against Black Americans remains visible in business, education, law enforcement, housing, healthcare, and elsewhere—and with startling frequency.

A hard road to travel

Black professionals and technology

One notable differentiator between Black business leaders and their White counterparts, according to the survey results, is their relationship with technology.

In terms of specific skills and knowledge helping to fuel their success, 60% of Black business leaders cite technical skills at a rate similar to the 63% response of White business leaders. But when it comes to regularly using technology in the workplace, larger gaps emerge.

Some 65% of White business leaders cite process efficiency as a tech-fueled outcome, while only 52% of Black leaders do. Revealing further gaps between the two groups, White respondents are more likely to identify tech as an enabler at significantly higher rates than their Black peers for: organization (59% versus 46%), innovation (59% versus 47%), productivity (58% versus 48%), and data-driven decision-making (57% versus 50%).

In the shift to working from home during the pandemic, Black business leaders struggled in similar ways and at similar proportions as White business leaders, in terms of internet connectivity, balancing work with caring for family members, and finding a quiet place to work. But Black respondents were 22% more likely than White respondents to see remote work as reinforcing existing inequalities in the workforce.

While 64% of White respondents expressed confidence that technologies and devices were developed with people like them in mind, only 47% of Black respondents felt the same. And 26% more Black American business leaders worry that some tech reinforces stereotypes and identity-based challenges.

White respondents were also 68% more likely to feel they had adequate access to technology and information. White respondents cited internet use and AI as critical to success at a 15% higher frequency than their Black peers. Even on the consumer front, White survey respondents said shopping-from-home tech tools provide improved access to goods and services at a 23% higher frequency than Black respondents.

Perspective

From childhood, many Black Americans are taught they must work twice as hard as their White counterparts in school and in the workplace. Being perceived as a threat means they have to constantly prove their capabilities, intelligence and work ethic due to negative stereotypes about Blackness. The price you pay for being Black is that you always overperform when you are the only one in predominantly White spaces. Again, Black people see overperforming as an investment in their own survival.

In the workplace, “occupational segregation,” which describes the perception that a Black individual is a better fit for a low paying job than a White person. Inherently, there is a cost of doing business in America while being Black—known within the community as “Black tax.”

There are two different meanings of the term “Black tax.” One definition used in Africa and some US Black circles is giving money to various family members in order to support them. The other definition is the belief that Black people need to work harder to get the educations they deserve, land jobs worthy of their talents, and begin to invest in their futures.

Black tax is a psychological phenomenon referring to the psychological weight Black people carry over their lived experiences. The Black tax is also the financial cost of conscious and unconscious anti-Black discrimination. How much is your organization collecting in Black tax?

Black representation lags in society

According to the survey, only half of Black business leaders describe the quality of their early education as good or very good compared to 75% among a parallel group of White business-leader respondents. This racial gap in educational quality persists but narrows during higher education, with 61% of Black Americans endorsing the quality of their undergraduate education versus 80% among White respondents, and 71% at the post-graduate level versus 82% for White leaders.

We asked business leaders about the extent to which consumer marketplace products and services are tailored to meet their needs and aspirations. For the White business leader respondents, the answer was 57% or better, whether that’s in reference to in-person, digital, customer service or entertainment experiences, such as movies and television. But for Black business leaders, the rate in each area was far lower—between 32% and 40% across the board. This stark reality illustrates not only the alienation felt by many Black Americans as consumers in society, but the missed opportunity for businesses to meet the market needs of a significant and important market segment.

“Black people are not dark-skinned White people.”

—Tom Burrell

Marketing, advertising and media are also areas where Black respondents indicate far lower representation than their White counterparts. Only 37% of Black Americans feel they are accurately represented in social media, versus 61% for White respondents; and just 32% of Black respondents feel themselves appropriately represented in advertisements, versus 63% for Whites.

When it comes to government, gaps in representation are even more alarming. Among White business leaders, 55% feel people like them are represented in federal government, 63% in state government, and 76% in local government. Among Black respondents those figures are miniscule—only 11% representation in federal government, 14% representation in state government, and 31% in local government.

All of this combined may explain why Black American business leaders feel less able to positively influence the future than their White peers. Examples include influence related to their careers (68% of Black business leaders versus 83% of their White counterparts), their family (61% versus 75%), or their community (35% versus 44%).

Quality of education

Take action now

The contributions and talent of Black Americans in business is undeniable. Whatever progress has been made to end discrimination and provide equal pathways to success, it isn’t enough; much work remains to be done.

Organizations cannot solely depend on Black employees to drive the work of inclusion. There must be leadership accountability, allyship with real action and the ability to challenge cultural norms. Organizations must act with purpose and intent.

Organizations asserting leadership in this area are able to access talent and drive performance, leveraging a diversity of ideas, experience, and perspective. But commitment to equity must begin at the top and extend throughout the organization. Anti-racism and inclusiveness is not a choice, it is a requirement.

Senior business leaders must step in and advocate to expand opportunities for Black professionals.

Five ways business leaders can commit to a culture of anti-racism

1. Prioritize representation

Black leaders need to be given opportunities for visibility across the organization, with a voice in all areas from strategy to implementation to talent development. Providing prominent role models is essential for young talent and others as they build their careers.

2. Expand education

Providing opportunities to Black talent at early stages sets a foundation that can place all employees on equal footing. Community engagement is essential to successfully enhance educational opportunities and preparing emerging leaders for success. Options for how and where to engage are broad; what’s required is commitment and staying power. Erasing bias isn’t a short-term effort.

3. Strengthen on-the-job training and coaching

Data confirm that these areas are significantly under-deployed in support of Black Americans in the workforce. Organizations and leaders urgently need to do more. Training and upskilling offer a valuable opportunity for growth. Direct one-to-one mentoring and sponsorship can inspire, engage, and enhance effectiveness of other efforts, while providing new opportunities for Black employees to build professional resiliency.

4. Make technology available

Access to technology is one of the most essential resources for today and tomorrow. Organizations must invest in embedding tech tools throughout the workforce – and that technology needs to be inclusive. Including all constituencies in the effort to improve technology capability will expand use and effectiveness.

5. Reinforce D&I objectives through leadership and advocacy

With stubborn cultural and societal obstacles still in place, the most senior business leaders must step in and advocate to expand opportunities for Black professionals. This is not a new discussion, nor is it an area likely to be resolved simply, easily or quickly. But difficult challenges are where leaders – as brands, as businesses, and as individuals—differentiate themselves. But there’s no better time to refocus and redouble your leadership efforts than now.

Moving forward

Arthur Chan once said, “Diversity is a fact. Equity is a choice. Inclusion is an action. Belonging is an outcome.” Creating workplaces that are inclusive of Black people will enable companies to retain a diverse workforce and bolster innovation. Blackness is race, ethnicity and culture all rolled into one category.

When Black workers feel psychologically safe and comfortable being themselves, they bring greater authenticity and better performance to their workplace.

We must choose to celebrate and understand Black culture not just in February, but every day of the year, because acknowledgment and respect allows organizations to truly be inclusive. Black representation and relevance matters, and should always be reflected in workplace culture.

Meet the authors

Brandi Boatner, Manager, Digital & Advocacy Communications, IBM CHQCindy Anderson, Global Executive for Engagement and Eminence, IBM Institute for Business Value